|

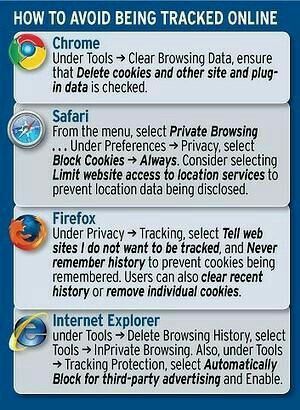

Now you may not care if some anonymous company knows what sites your browser visited. This data is collected anonymously (well, semi-anonymously) and is designed to show you ads you might be more interested in than, say, how to reduce belly fat or get a cut rate loan. Many people, some of them diehard privacy advocates, prefer targeted ads. I'm here to tell you that this debate is not about advertising. It's about something much bigger and potentially much more profitable. It's about creating profiles of your behavior online and designing algorithms to make decisions about you based on that behavior. It's about gathering that data, mining it, and selling it to the highest bidder, over and over again. Today that data is used almost exclusively to deliver ads. But how will it be used tomorrow? 1. Oh the prices you'll pay Variable pricing exists in many forms outside the Internet. Anyone who's booked an airline ticket can tell you prices vary wildly depending on when you buy your seat. Soda at the convenience store next to the beach costs more than it does at the supermarket down the street. Bad drivers have to pay more for their auto insurance. Most people understand these things; they're all pretty obvious. But should you pay more for a hotel room just because you used an Apple device to search for it? You might. In fact, as the Wall Street Journal has reported, Mac users who booked hotel rooms on Orbitz paid an average of $20 to $30 a night more than those who visited the site using a Windows PC. They weren't charged more for the same rooms, but they were shown more expensive rooms – which they then booked. Why? Because every Web site you visit knows what operating system you're using. It receives that information automatically, along with other data that can be used to uniquely identify your machine, such as your IP address. (That's the semi-anonymous part I mentioned above.) Add profile data gleaned from behavioral tracking cookies, and the information they can use to decide what prices to show you becomes much richer. If you've provided your phone number or email address, they can add even more info about you, including data from public records databases and your offline purchase history. But Web sites don't need to know your name to determine what type of consumer you are. All they need to know is which demographic “buckets” you fit into. You'll never know you're being shown a different deal than your next door neighbor. And the data they use to make these decisions is not at all obvious. 2. You are more than the sum of your “Likes” A few months ago a group of Cambridge University researchers published the results of an experiment using a Facebook app that tracked everything its users “Liked” on the social network. They surveyed the app's users as to their demographic information, then plotted correlations between who they said they were and what they did on Facebook. Using just Facebook Likes, the researchers were able to determine with impressive accuracy a person's gender, age, race, sexual tendencies, political leanings, drug habits, and more. Some of the correlations were, frankly, strange: People who like curly fries tend to have higher IQs. Some made intuitive sense: Men who like the TV show “Glee” are probably gay. And some were both: Fans of the death metal band Slayer were more likely to smoke cigarettes. This is what data mining is about – making correlations between two or more seemingly unconnected bits of information. It's how tracking companies like ToneFuse know that John Lennon fans are more likely to own cats, or that Rhianna fans are good candidates for buying a cut-rate cruise. It's how the FBI and other three-letter agencies are hoping to track crooks and terrorists before they strike. In other words, you don't have to visit Marlboro.com for advertisers to detect your nicotine addiction. They'll buy that information for pennies from a data broker who inferred those conclusions based on other things you've done online. 3. Weblining for fun and profit If you've ever applied for a job, a loan, insurance, or just about anything else in the past couple of years, you probably started by going online and filling out a form. The site where you did that could easily have access to one of your profiles. If you've been tagged as a gay smoker by some data mining company, the employer or the bank won't have to ask you if you enjoy the occasional puff – they'll already know. Some online banks are already starting to use Facebook profiles as a way to identify poor credit risks. If your friends are deadbeats – or at least, fit the profile of likely deadbeats – you probably are one too. Why risk it, when it's safer to just issue an immediate rejection? In the real world, refusing to sell insurance or offer loans to residents of certain neighborhoods – typically containing a high percentage of minorities -- is called “redlining.” It's illegal, though difficult to prove. Online it's called “Weblining.” Aside from some regulated industries (like health and financial), Weblining is not illegal. And proving it? Good luck. This isn't just theoretical whining from privacy nut-jobs. Both the Network Advertising Initiative and the Digital Advertising Alliance have agreed to not collect or use tracking information “for the purpose of making an adverse determination of a consumer’s eligibility for employment, credit standing, health care treatment and/or insurance underwriting.” Bravo to the NAI and DAA for pro-actively adopting those restrictions. But these principles are voluntary and only apply to NAI and DAA members. What about the 600+ tracking companies that aren't members of the NAI or the DAA? What are they going to do with your data? Who's watching them? Who's going to stop them? If you're a fan of Slayer but you don't smoke cigarettes, will you still be shown a higher rate when you go to renew your health insurance online, just because the insurance company assumes you do? Or let's say you operate an 'exclusive' online club with a very restrictive membership policy. How hard would it be to exclude applicants for being of the wrong ethnic, sexual, or political persuasion? Not hard at all. 4. Two wrongs could still undo your rights As I've written about a few times before, online data profiles are often wildly inaccurate. You may be a spindly old crone who never leaves the house, but data tracking company X thinks you're a NASCAR dad who smokes cigars and eats nachos. You may be pegged as a trendy soccer mom when you are instead a manly intrepid reporter who is neither tarnished nor afraid. Multiple people may use the same browser, confusing the profilers. Or maybe you're clever and visit Web sites totally at random to pollute their data and throw them off the scent. It doesn't matter. You might receive benefits you otherwise wouldn't – like coupons for that big party size bag of Doritos. Or you might be needlessly penalized by a car insurance company that decides you're a curly fries-eating metal-head who can't be trusted to obey the posted speed limit. But your profile data could still be used to make decisions about you in invisible ways. It's a safe bet that tracking technology will get far more precise and accurate over time. Whether that's a comfort or a worry, I'm not sure yet. But I am sure we need a way to just say no to tracking, and for our choices to be honored. So How Do I Keep From Being Tracked?

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

August 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed